The 6th Sunday after Pentecost offers riches from the Epistle to the Romans and the Gospel of Saint Mark. The 1962 Missale Romanum presents these readings not in isolation, but as a liturgical unity, revealing the depth of Christian life in its paschal dimension: dying and rising in Christ, and being fed in the desert by His merciful hand.

A personal note. I derive great satisfaction in writing these essays. I gain a lot from preparing them. St. Augustine, when commenting in the Gospel reading for this Sunday (s. 95), which details the second feeding of the multitudes, the 4000, says:

When I expound the holy scriptures to you, it’s as though I were breaking bread to you. For your part, receive it hungrily, and belch out [eructate] a fat praise from your hearts; and those of you who are rich enough to keep excellent tables, don’t be mean and lean with your works and good deeds. So what I am dishing out to you is not mine. What you eat, I eat; what you live on, I live on. We share a common larder in heaven; that, you see, is where the word of God comes from.

Latin eructo is “belch, vomit up”. Thank you for bearing with my burpings.

Perhaps some explanation is in order. First, in the ancient world, to blech at the table is a sign of appreciation for the food and host. Remember the scene in the movie Ben Hur (the 1959 version) when in Sheik Ilderim’s tent Judah is prompted to burp? Also, the verb eructo, -are is deeper than you might think.

We should take this “belching” as a metaphor to meditating on Scripture.

“How’s that again?”, you might be asking.

One way that we speak about meditating on Scripture is “to ruminate”. Literally, rumination is what cows do when they chew their cud. Cows and other ruminants (like giraffes) regurgitate and chew again previously swallowed food to get more nutrients out of it. Perhaps on the analogy of being able to “ruminate” about Scripture, kosher laws permit Jews to eat ruminants. Pigs are not ruminants, so they are not kosher.

Taking this into the Catholic liturgical realm, the Introit chant of Masses of the Blessed Virgin include the verse from Ps 45(Vulgate 44):1: “Eructavit cor meum verbum bonum: dico ego opera mea regi. … My heart belched up a good word/utterance: I declaim my works/verses for the king”. Or as the RSV puts it, more delicately, “My heart overflows with a goodly theme; I address my verses to the king”.

Thus, it is with the image of throwing up that we engage with the Blessed Virgin at the beginning of Masses in her honor, for she pondered, ruminated over the words of the angel. She was silent and chewed over what she had heard. Then she hurried to Elizabeth and burst forth in the magnificent Magnificat.

I could continue to chew the cud of this image for the rest of my allotted space, but we must move forward.

Today we hear St. Paul’s words to the Romans (6:3–11). They confront us with the startling truth of baptism: it is a death.

“An ignoratis quia quicumque baptizati sumus in Christo Iesu, in morte ipsius baptizati sumus?… Do you not know that all of us who have been baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into His death?” (v. 3).

Paul is not being rhetorical for the sake of style. Rather, he is recalling the Roman Christians, and us by extension, to the deepest reality of our identity in Christ. Baptism is no mere rite of passage or symbolic ceremony. It is a burial. The Latin “consepulti enim sumus cum illo per baptismum in mortem… For we were buried therefore with Him by baptism into death,” (v. 4) strikes with the ring of a hammer on your tombstone. The verb con-sepelio, “to be buried together with,” conveys that the Christian life does not begin with improvement but with death, a radical end to the life of sin.

The old man is not healed. He is executed.

This Pauline doctrine is affirmed in the Catechism of the Catholic Church:

“The immersion in water symbolizes not only death and purification, but also regeneration and renewal. Thus, the two principal effects are purification from sins and new birth in the Holy Spirit” (CCC 1262).

What is accomplished in baptism is not merely external. It is not an accessory to a life already underway. It is a new birth into a life that did not exist before, “in novitate vitæ…in newness of life.”

This newness is not novelty in the sense of time, but in kind. It is the life of Christ Himself. “Ut quomodo Christus surrexit a mortuis… ita et nos in novitate vitæ ambulemus … Just as Christ was raised from the dead… so we too might walk in newness of life” (v. 4). Paul presses this mystery deeper: “Si autem mortui sumus cum Christo, credimus quia simul etiam vivemus cum eo … If we have died with Christ, we believe that we shall also live with Him” (v. 8)

This is not abstract mysticism. It is the foundation of our identity. Our hope is not in our own efforts, but in our union with the dying and rising Christ. This is why Christian moral life is not a matter of Pelagian striving, but of a paschal identification: I have died with Christ, and now His life lives in me (cf. Gal 2:20). We are cooperators, literally “doing the work together” (Latin archaic form of cum, com- “with” and operari “to work”). Hence, all that we do which is meritorious is meritorious because it is from Him, by Him in us, and for Him.

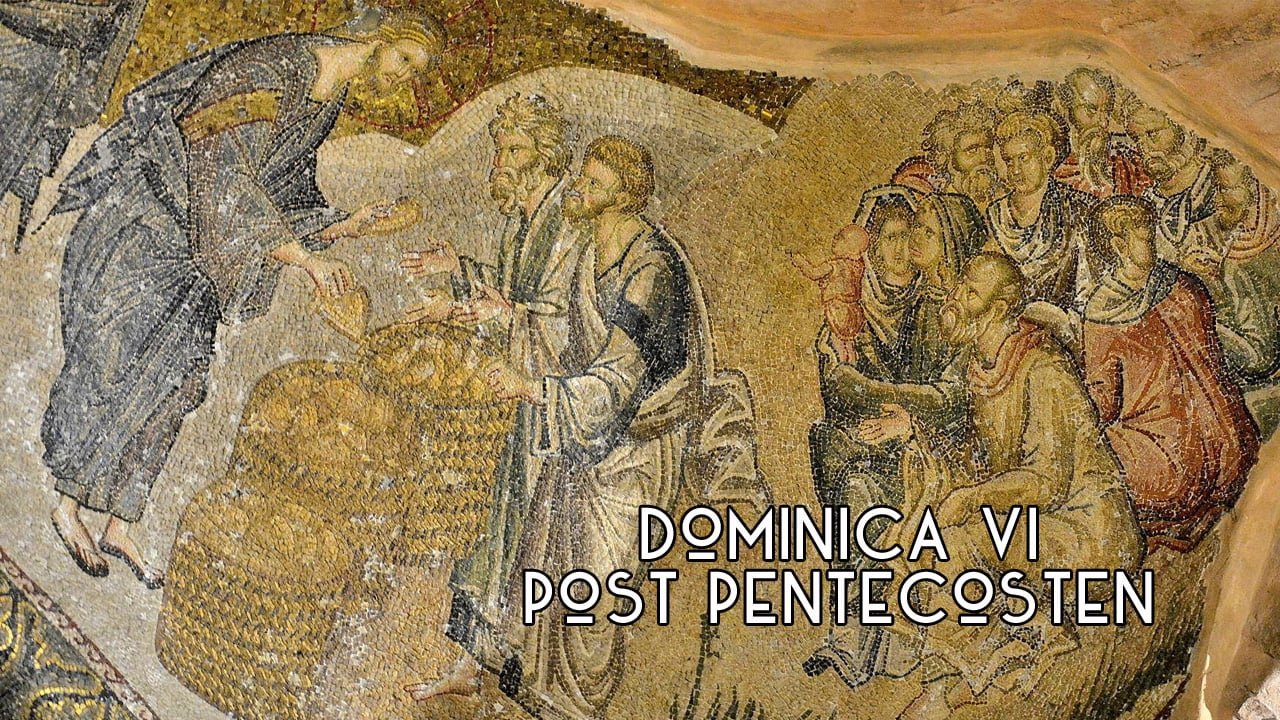

This theme finds its echo and fulfillment in the Gospel of Mark (8:1–9), which recounts the miraculous feeding of the four thousand.

Unlike the earlier feeding of the five thousand, which took place among the Jews, this miracle occurs in Gentile territory. The Lord, after healing and teaching, looks upon the hungry crowd who followed him out into the middle of nowhere with a gaze of divine compassion. “Misereor super turbam … I have compassion on the crowd” (Mark 8:2). The verb misereor expresses more than pity. It denotes a gut-wrenching, visceral mercy. The Greek verb used, σπλαγχνίζομαι (splagchnízomai), derived from the wonderful sounding πλάγχνα (splágchna), refers to the entrails, speaking of burping, believed in ancient times to be the inner seat of emotion. This is not detached sympathy, but the aching mercy of the Word made flesh.

He sees their hunger, and He desires to feed them. He hungers for them. He hungers for us to hunger for Him and to be fed upon his very Person. When in John 6 (the same chapter which recounts the first miraculous feeding) Christ says we must eat His flesh, the Greek verb is trógo, “to gnaw”. Looking up τρώγω in Liddell-Scott-Jones (aka “Middle Liddell”) we see it means “to munch, of herbivorous animals”. We have returned to our theme of rumination. There is a slap-your-face reality check in “gnaw”. Jesus meant exactly, “eat”, not just “think about” His flesh. He means that too, but far more, and in a literally visceral sense.

Let’s keep moving.

The Lord asks, “Quot panes habetis? … How many loaves do you have?” (v. 5). The question is not born of ignorance. Christ, the Logos, isn’t asking for mere information. He asks in order to draw the disciples into participation. He invites them into His plan. “Septem … seven loaves” is the answer. Seven is the biblical number of fullness and covenantal completion.

Christ could have created bread from nothing, as He turned water into wine at Cana. But He chooses instead to work through smallness, through the ordinary, through human cooperation. After all, someone had to let go of his bread and fish. We have to let go of the “old man” and let him die.

Also, seven is the number of “jubilee”. We are observing a Jubilee Year in the Church as I write. The ancient Jubilees of the Jews were times of renewal and freeing from debt. Consider the gnawing emptiness of debit, like a hunger that has no repast. It is not going too far to push this image of the hungry people following Jesus into the countryside being set free in this mini-Jubilee moment of the feeding of the multitude. It also might link us back into the Epistle with its imagery of being empty (in death from sin) and rising to new life (fed by the Bread from Heaven).

Mark tells us that Jesus gave thanks (eucharistēsas) and broke the bread. The Greek here is rich with Eucharistic connotation. He gives thanks, He breaks, and then “edidou… He kept on giving”. The imperfect verb form indicates repeated, continuous action. He did not simply give once and stop. He gave, and He gave, and He gave again. The miracle unfolds through the hands of the disciples. They become the distributors, coworkers, the stewards of the divine gift.

“Et manducaverunt, et saturati sunt … And all ate and were satisfied” (v. 8). From seven loaves and a few fish came fullness. They were given not mere sufficiency, but superabundance. Seven baskets of leftovers remained, each one heavy with grace. The miracle points forward to the Eucharist, the perpetual feast of Christ’s body, given for the life of the world.

Pius Parsch, that master of the semicolon and commentator of the 20th century Liturgical Movement, reflected on this Sunday.

[T]hrough baptism I became a hand of Christ. The hand partakes in all that concerns the person of whom it is a member. If the person is rich, the hand will be soft and smooth; if the person is poor, the hand will be rough and calloused. Visualize the hand of Christ. It worked wonders. Upon the Cross it was pierced; it was placed in a grave; at the resurrection its scars shone brightly; at the ascension it entered heaven’s glory. Now at baptism you became a hand of Christ; therefore you are reliving all that Christ did and suffered… And as Christ dies now no more, so also you are dead to sin, alive always to God.

This perhaps might be a starting point for priests to ponder. Time and again, during the distribution of Communion I’ve been stuck by the fact that God has made me His hand. Looking at the Host in the hand that was consecrated with Chrism for this moment, the priest knows, “I became a hand of Christ.”

The Latin for hand, manus, often used in expressions like manus Dei, denotes agency, instrumentality, power in action. Here, the priest’s hand becomes not merely his own but the hand of Christ, the conduit through which grace is given. This is not an exaggeration of priestly identity. It is the theology of the Church: the priest is not the source but the minister. Christ feeds His people with Himself through human means.

And not only priests. Every baptized soul, conformed to Christ, becomes in some way an instrument of His mercy. The small offerings of our time, our patience, our prayers, our fishes, loaves and lives are not discarded. They are taken up, blessed, broken, and distributed. And when we are in fragments we are gathered up, as we hear after the parallel feeding of the 5000 in John 6:12: “colligate quaesuperaverunt fragmenta ne pereant… gather up the remaining fragments lest they be lost”. The Lord who once fed five thousand and four thousand continues to feed His people today, using what is small and seemingly insufficient. He uses trembling hands and willing hearts to accomplish His purposes. The fragments are not accidents, afterthoughts.

The Collect for this Sunday underlines this theology of divine initiative and human cooperation:

Deus virtútum, cuius est totum quod est óptimum: ínsere pectoribus nostris amórem tui nóminis, et præsta in nobis religiónis augméntum; ut, quæ sunt bona, nútrias, ac pietátis stúdio quæ sunt nutríta custódias.

LITERAL:

O mighty God of hosts, of whom is the entirety of what is perfect: graft the love of Your Name into our hearts, and grant in us an increase of religion; so that You may nourish the things which are good and, by zeal for dutifulness, guard what has been nourished.

Here we are back with imagery of nutrients, nourishing. We keep chewing over this theme.

The Collect asks the Lord to plant in our hearts the love of His Name and to grant us an increase in the virtue of Religion. It affirms that the good in us is not self-generated. It is planted, nourished, and preserved by divine action. The prayer also asks that we cooperate in pietatis studio, with the zeal of “piety”. What is begun by God must be preserved by grace and guarded by human vigilance. The Roman sense of pietas is especially the honor we are bound to show toward our parents, especially our father, but by extension to children and the one’s fatherland, patria. In liturgical language, when pietas is applied to us humans it is the due respect we show supremely to God the Father, but also to His children in the foreshadowing of our true heavenly patria, the Church. When in liturgical texts we talk of the pietas of God, we are talking about His mercy. God cannot be under obligations, as we can be, but He has made us promises. He will be true. In our Collect there is a strong conceptual link between pietas and religio.

In this longish verbal eructation, this Sunday we find the mystery of the Christian life made manifest: the movement from death to life, from hunger to satisfaction, from insignificance to divine agency. We are baptized into Christ’s death so that we may rise with Him. We are fed with His Body so that we may live by His life. We are small and insufficient, yet He multiplies what we give. He does not wait for us to be strong. He works precisely through our weakness.

Christ says, “I have compassion on the crowd.” He still does.

Lord, make us better hands.